Research

Research

Book Project

Why Women Vote: When and How Clientelism Closes the Gender Turnout Gap (Based on Dissertation)

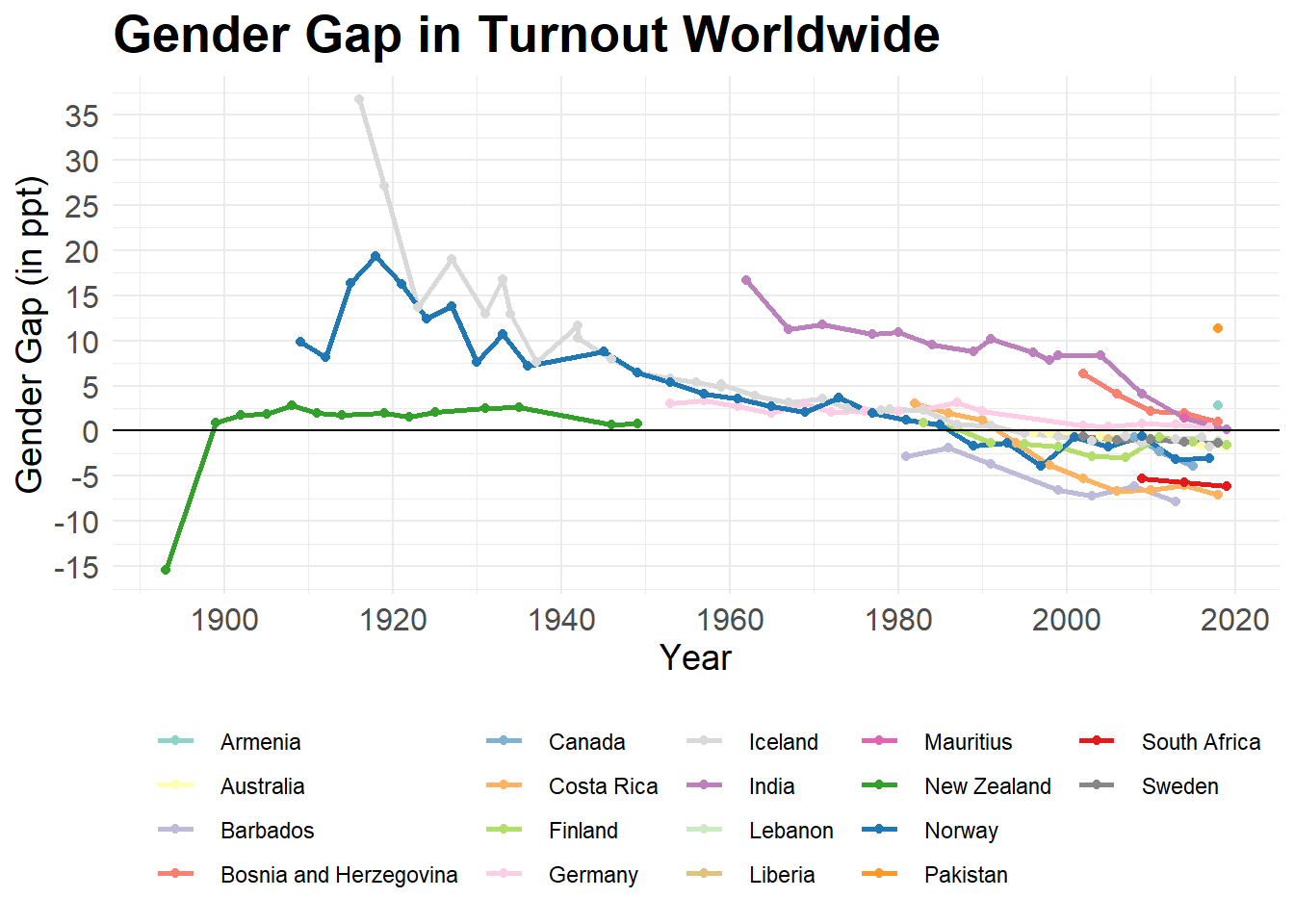

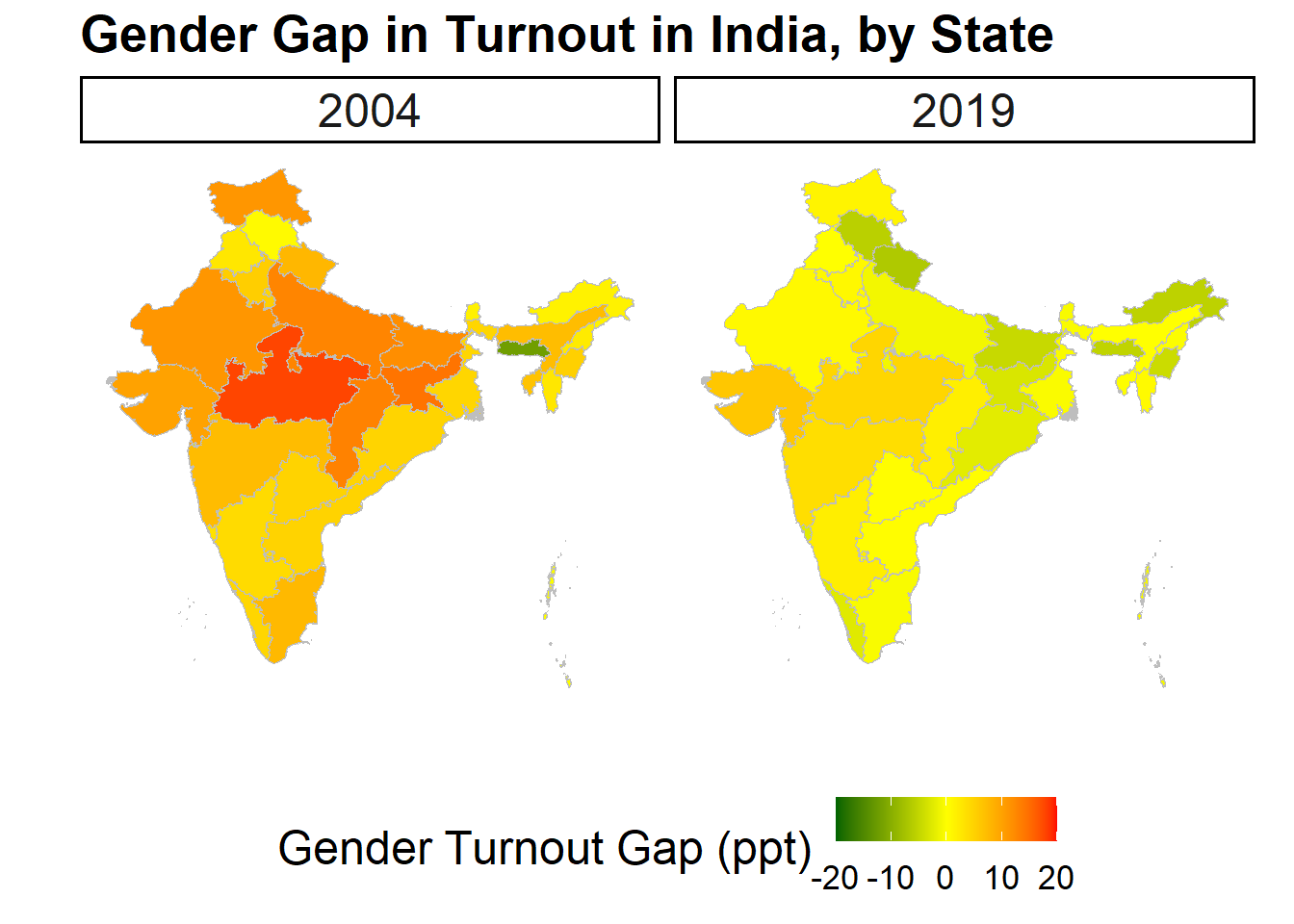

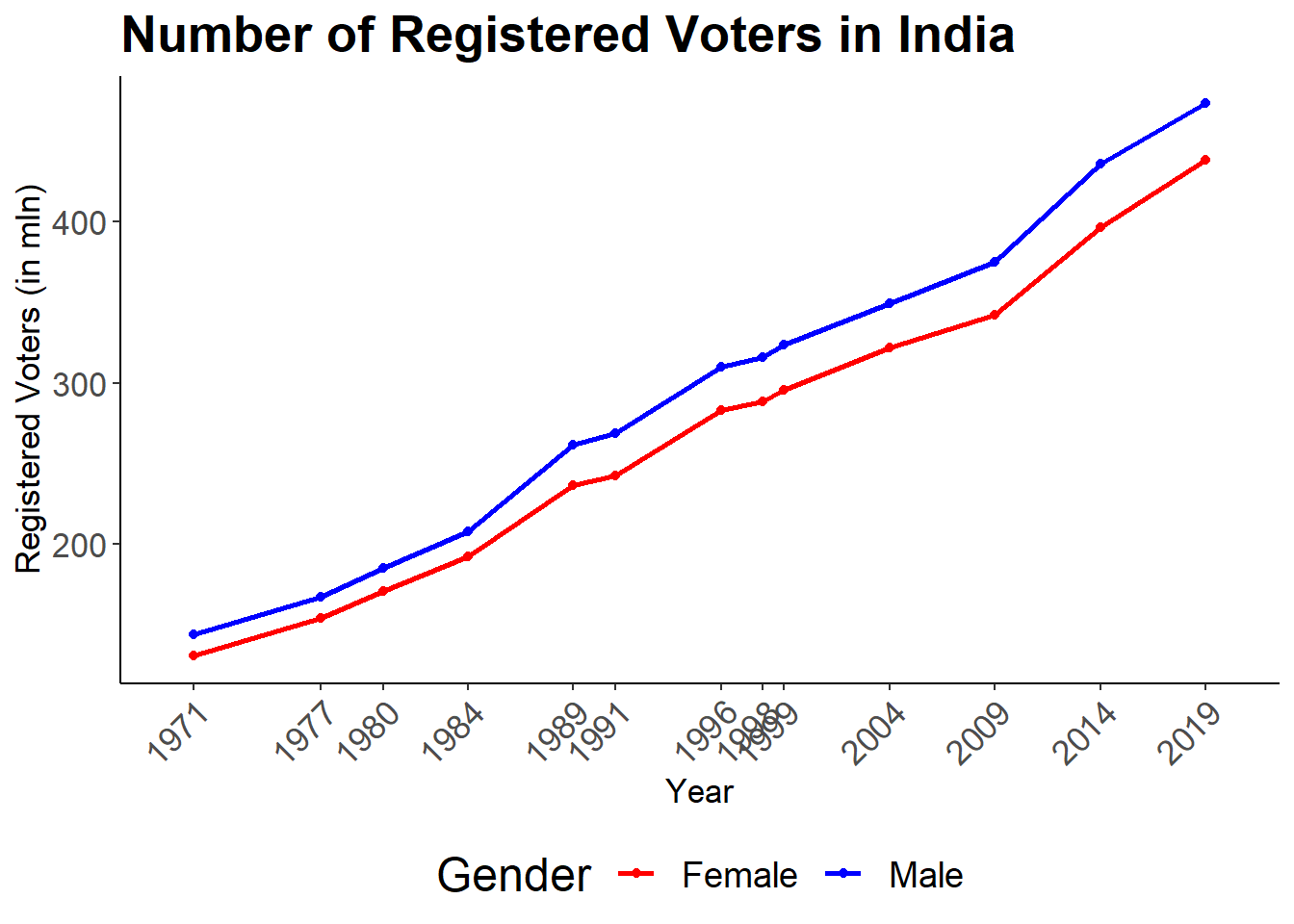

When do women turn out at equal rates to men? My book project re-investigates this question in the context of developing countries. Existing theories of women’s political participation are largely resource-based, yet in many developing countries, women turn out at par with men in the face of low levels of economic development and female labor force participation, and despite gendered differences in individual-level resource endowments. Based on an in-depth investigation of India, I argue that there is a second path to women’s equal political participation that does not rely on individual-level resources, but instead depends on clientelism and household support for female turnout. Where households are supportive, they can bridge the resource gap for women. Household support, in turn, depends on high levels of clientelist returns to a vote. I provide several pieces of empirical evidence from India consistent with this theory, based on two original surveys and a novel panel dataset on the extent of clientelist party mobilization. I show that female turnout is higher in a poorer and more clientelist state than in a better developed but less clientelist state, and that household support for female turnout – but not other forms of political participation – is high under clientelism. I also demonstrate that increases in levels of clientelist mobilization – measured as a rise in the number of ethnic groups targeted by clientelist parties – leads to smaller gender turnout gaps at the constituency level across several states. My research has important implication for our understanding of the relationship between development and female political participation, as well as the consequences of clientelism.

Working Papers

How Clientelist Party Mobilization Closes the Gender Turnout Gap: Theory and Evidence from India

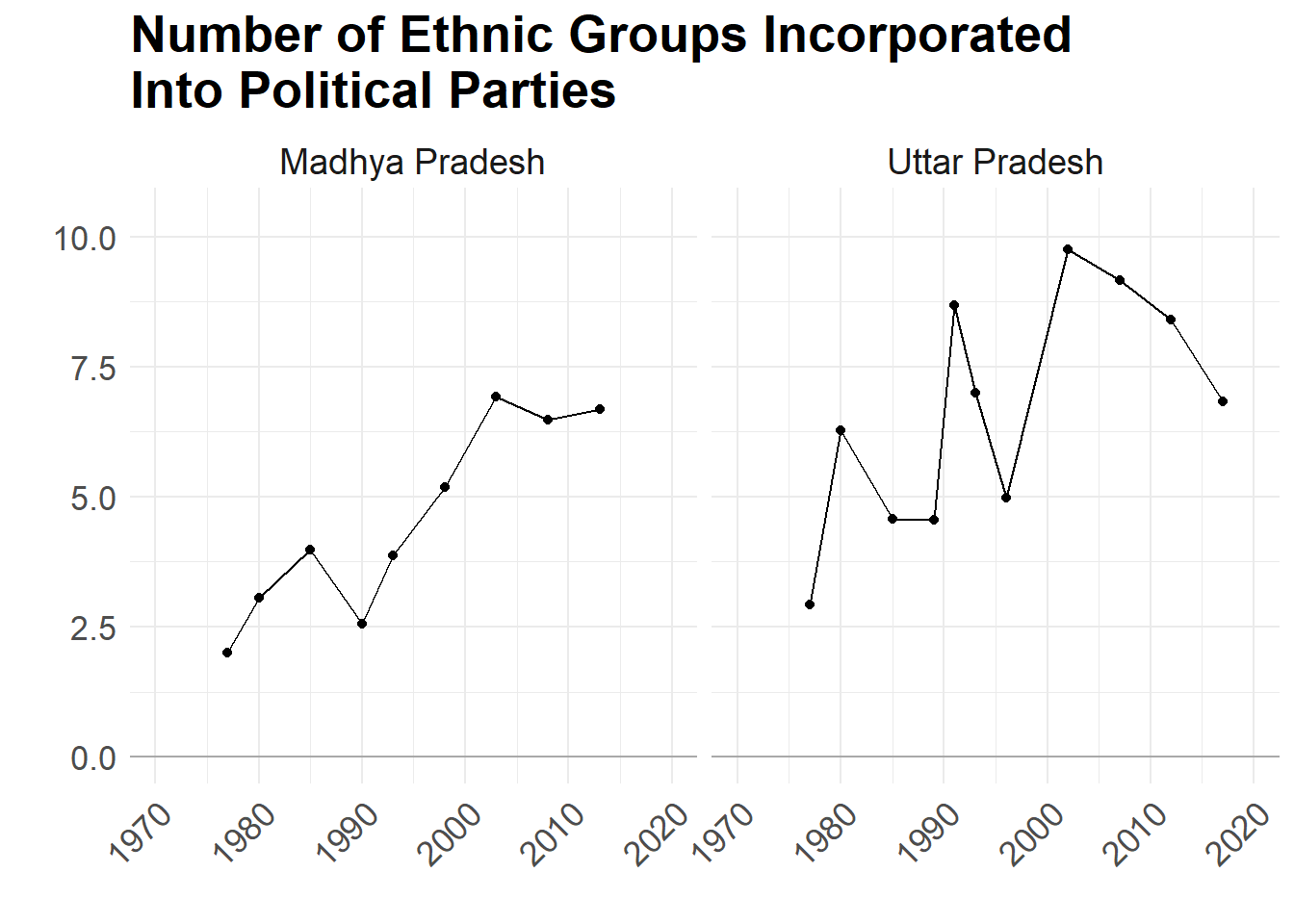

When are returns to a vote high enough to mobilize female turnout? I develop a typology of clientelist regimes that posits that both the sequencing of the clientelist exchange as well as the source of the clientelist resources determines the value of a vote. Returns to a vote should be highest when clientelist parties rely on post-election resource sharing arrangements that provide selective post-election access to state resources; and lowest when clientelist parties instead bank on privately funded electoral handouts. I test this theory in India, a particularly puzzling case of gender turnout parity. I use the fact that in India, ethnicity is politically salient and clientelist parties purposefully incorporate some ethnic groups into their leadership, while excluding others, to send signals about the future distribution of state resources. Members of ethnic groups who have a co-ethnic in any party’s leadership will expect the highest returns to a vote, and therefore be most likely to support female turnout. Using a novel panel dataset on the number and types of ethnic group incorporation into state-level party leadership of all major parties for all state elections in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh from 1977 through 2007, I show that a) the number of ethnic groups incorporated went up over time, with considerable spatial and temporal variation; and that b) a rise in the number of politically incorporated ethnic groups before an election leads to a drop in the gender turnout gap during the election.

Exclusion Before Elections: How Faulty Voter Lists Disenfranchise Women in India

Faulty voter lists raise concerns about the health of democracy: incomplete lists effectively disenfranchise eligible adults, while inaccurate lists containing errors and deadwood potentially open the door to voter fraud. Yet we know little about the quality of voter registers outside of the U.S. Using two full village censuses and voter list annotations, I investigate the completeness and accuracy of voter list in India, the world’s largest democracy. I find that voter lists simultaneously exhibit under-enrollment of eligible adults as well as deadwood. Women and young adults were the most likely to be unenrolled. By contrast, income, religion, and caste identity were uncorrelated with voter registration. I trace how the perverse incentives faced by street-level bureaucrats in charge of maintaining voter lists lead to growing deadwood on the register and, as a consequence, to rising under-enrollment. In addition, I provide evidence that patri-local marriage norms, together with the hyper-local nature of voter lists, can explain at least some of the gender gap in enrollment.

Voting Her Mind or Voting with the Family? Investigating Agency and Vote Choice in India

(with Rahul Verma, CPR, Delhi)

Download Working Paper (under review)

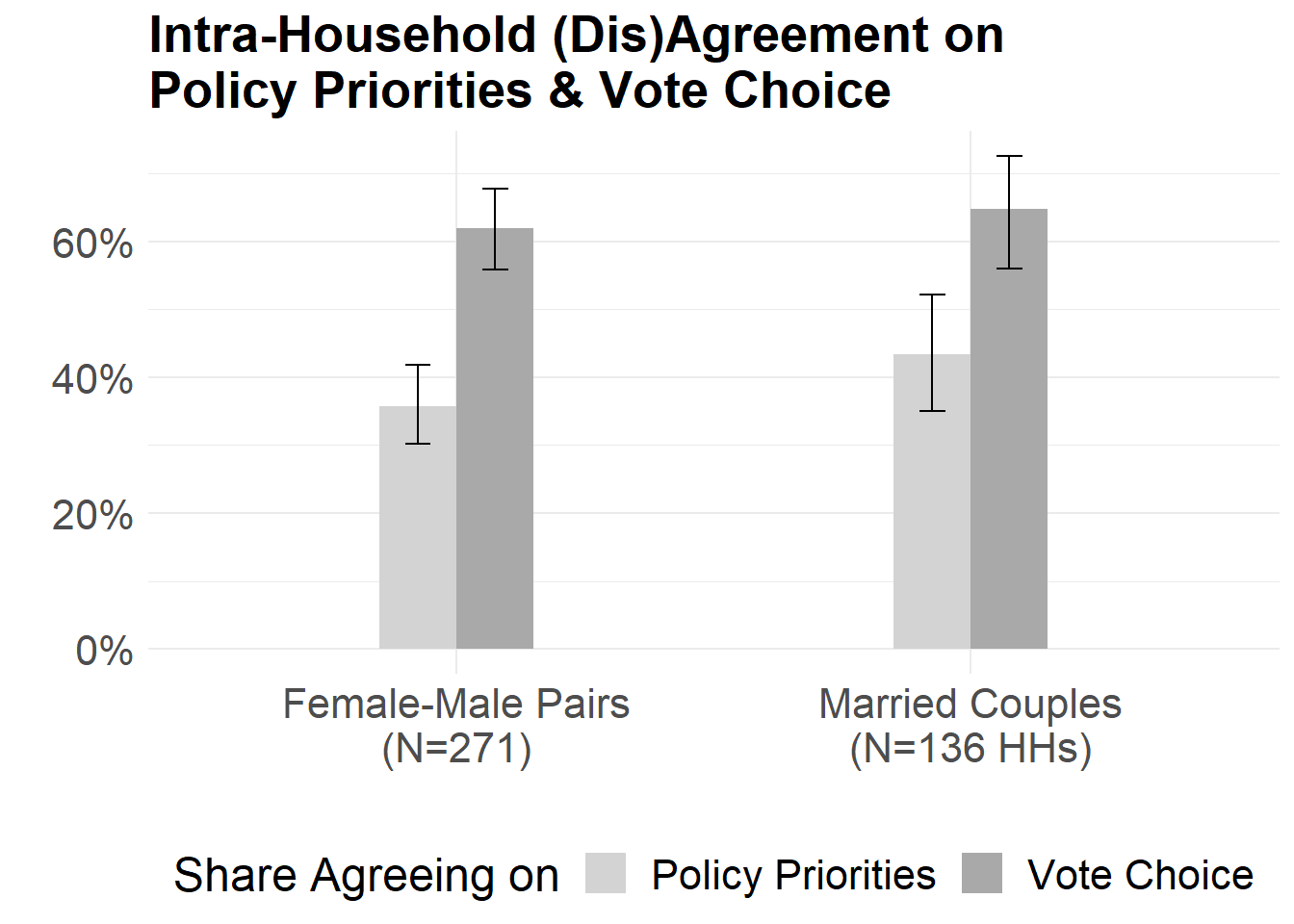

How much agency do women hold over their vote choice? Where individuals are socially and economically dependent on the household, members coordinate on a host of behaviors, including political participation and vote choice. But how do we measure agency over vote choice? In many developing countries, policy preferences do not map neatly onto parties or candidates. Voting for the same party despite differing policy preferences can be rational in such settings. Vote pooling within the household, therefore, is not in and of itself proof of a lack of women’s agency. We overcome this problem by using a novel measure of preference-consistent voting that checks whether women’s vote is internally consistent, i.e., whether women voted in line with their own stated policy preferences. Contrary to expectations based on the literature, we find that women are no less likely than men to vote in accordance with their stated preferences; and that household disagreement on policy priorities does not predict women’s preference-consistent voting.

Work in Progress

Holding Up Half the Sky? The Influence of State Actors on Gender Norms in Rural India

(with Anjali Thomas, Georgia Tech; Charles Hankla, GSU; Sayan Banerjee, Texas Tech)

In much of the developing world, girls’ education lags behind boys’. Our research seeks to shed light on the role that cultural norms play in perpetuating this problem. Specifically, we investigate whether state actors – elected politicians or bureaucrats – can change families’ expectations of the value of educating their duaghters. Appeals by state actors might be particularly effective in updating parents’ beliefs about the social acceptability and future payoffs of investing in girls’ education because of state actors’ perceived knowledge of the local context as well as their perceived influence within it. In a large-scale field experiment in Bihar (N=2,200), one of India’s poorest states with one of the lowest female literacy rates, we use video appeals encouraging parents to educate their daughters recorded by real-life state actors to test this. We vary tier of government, position, and gender of the state actor, and collect a host of attitudinal and behavioral outcome measures.

Work and the Vote: Does Welfare Expansion Improve Turnout?

(with Varun Karekurve-Ramachandra, USC)

(Data collection in progress)

Does the expansion of the welfare state increase or depress political participation in developing countries? In many developing countries, where state capacity for taxation is low and wealth redistribution therefore limited, the poor vote at higher rates than the rich because it is easier (and cheaper) for political elites to motivate the poor to turn out. Welfare provisions that improve the overall standard of living, therefore, might make it harder for elites to elicit turnout. On the other hand, prior research suggests that higher welfare provisions make the state more visible to ordinary citizens, particularly in rural areas, and therefore drive up expectations of political responsiveness and benefit provision. This could motivate more citizens to turn out to voice their demand for new (or continuing) benefits. We leverage the staggered rollout of India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS), the largest public works program in the world, to test whether positive income shocks for rural laborers affected turnout.

The Challenge of Measuring the Gender Turnout Gap